Reporter Betty Eppes says she feels bad about the tape, which was recorded without the author's knowledge.

|

| Photo: Mandel Ngan (Getty Images) |

The woman in possession of the only known audio recording of late author J.D. Salinger says she plans to have it cremated alongside her when she dies, Bloomberg reported on Thursday.

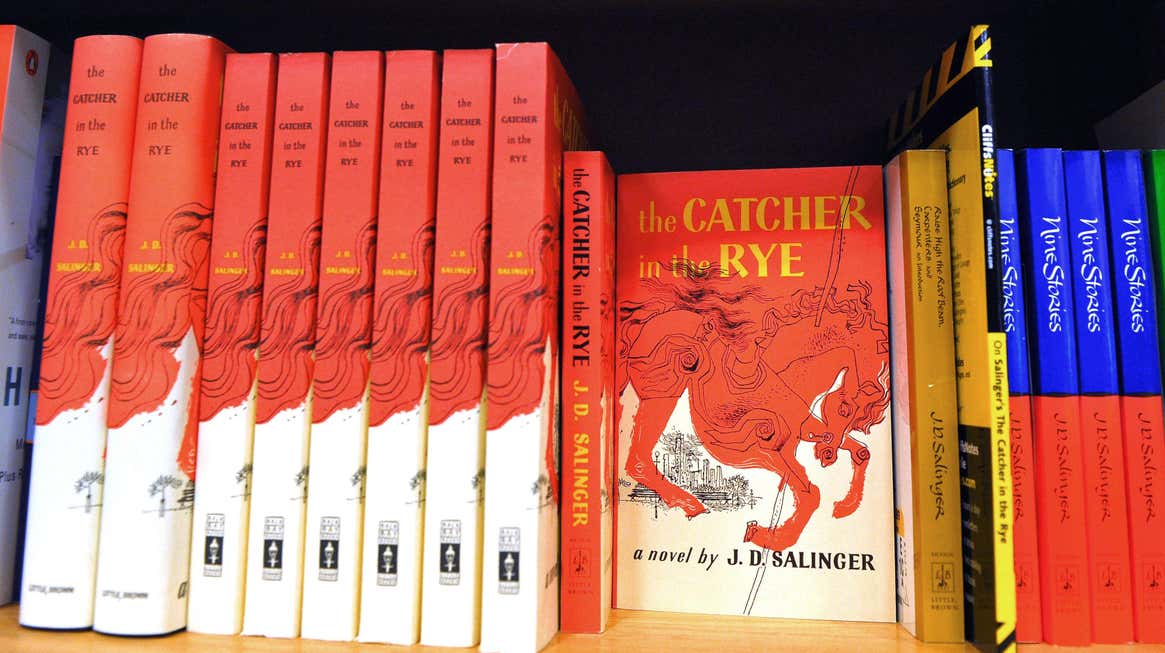

Then a reporter for the Baton Rouge Advocate, Betty Eppes managed to track down the notoriously private author at his home in Cornish, New Hampshire, in 1980. Salinger hadn’t published any new work since Catcher in the Rye, which came out in 1965; he hadn’t given any interviews in many years (while Bloomberg cites the last prior interview as occurring in 1953, he spoke with the New York Times in 1974). Eppes told Bloomberg that she had been looking to land one of the most difficult interviews possible and settled on Salinger over two competing candidates, Thomas Pynchon and brutal Ugandan dictator Idi Amin

As Bloomberg noted, it’s only relatively recently in historical terms that the public knows what authors sound like—before 1950 or so, authors were rather unlikely to be recorded talking, and even less likely for those recordings to survive. In one of the most famous examples, no known recordings of Nineteen Eighty-Four author George Orwell survive, rather inexplicably as he was a regular fixture on BBC Radio. It’s little surprise that the same is true of Salinger because, although he lived until 2010, he was deluged by fans and media requests after the publication of Catcher in the Rye and reacted by retreating from celebrity life as thoroughly as possible.

Eppes had an interesting way around this. She misled him. Eppes told Bloomberg that she had poked around talking to locals in Cornish to identify the author’s hangouts, as well as passed on a letter to him via the post office in which she introduced herself not as a reporter “but a novelist—tall, with green eyes and red-gold hair—who had no intention of ‘usurping any of your privacy.’” (One reason the request may have gotten Salinger’s attention: What author Joyce Maynard described as his predatory habit of grooming much younger women in the literary field.)

In the letter, Eppes told Bloomberg, she mentioned a possible meeting location at a local shopping center the next morning. Lo and behold, Salinger appeared and began talking, although Eppes never informed him she had a hidden voice recorder:

Lo and behold, the 61-year-old Salinger showed up the next morning wearing jeans, sneakers, and a shirt jacket. Eppes turned on the recorder and asked him if Holden Caulfield, his most famous character, was ever going to grow up. “It’s all in the book,” he said. She also asked about Salinger’s experience in World War II, whether he was still writing, why he refused to publish any longer, and whether he believed in the American dream. “My own version of it, yes,” he said.

In all, Eppes recorded 27 minutes’ worth of conversation with Salinger before some of the locals came over and tried to shake his hand. Angry, he stormed off back home.

A version of the interview was published in the Paris Review in 1981, but the audio has never been publicly released. Approaching an interview in this fashion would be a pretty serious violation of journalistic ethics without extraordinary circumstances, and this situation doesn’t fit the bill. To her credit, Eppes told Bloomberg she feels pretty badly about the whole thing.

Eppes told Bloomberg she had turned down a $500,000 offer from a “wealthy, interested foreign party” shortly after the publication of the Paris Review piece, and didn’t provide any audio to director Shane Salerno for his 2013 documentary, Salinger: “In the years after I did that, I came to regret it, terribly, terribly. I have spent many, many, many, many hours a day thinking about this. And, of course, it means an awful lot to me.”

A version of the interview was published in the Paris Review in 1981, but the audio has never been publicly released. Approaching an interview in this fashion would be a pretty serious violation of journalistic ethics without extraordinary circumstances, and this situation doesn’t fit the bill. To her credit, Eppes told Bloomberg she feels pretty badly about the whole thing.

Eppes told Bloomberg she had turned down a $500,000 offer from a “wealthy, interested foreign party” shortly after the publication of the Paris Review piece, and didn’t provide any audio to director Shane Salerno for his 2013 documentary, Salinger: “In the years after I did that, I came to regret it, terribly, terribly. I have spent many, many, many, many hours a day thinking about this. And, of course, it means an awful lot to me.”

“Sometimes, I wake up in the middle of the night and I think, ‘I stole that. I stole his voice,’” Eppes added. “You know that’s like stealing somebody’s soul, right? That tape is not mine to give or sell.”

Bloomberg reported that in a follow-up call, Eppes confirmed that she will adjust her will to ensure that the audiotape is cremated in her coffin after her death. The recording itself is currently in a safe deposit box.