A trust gap is growing between the public and AI developers. A new set of recommendations could help.

|

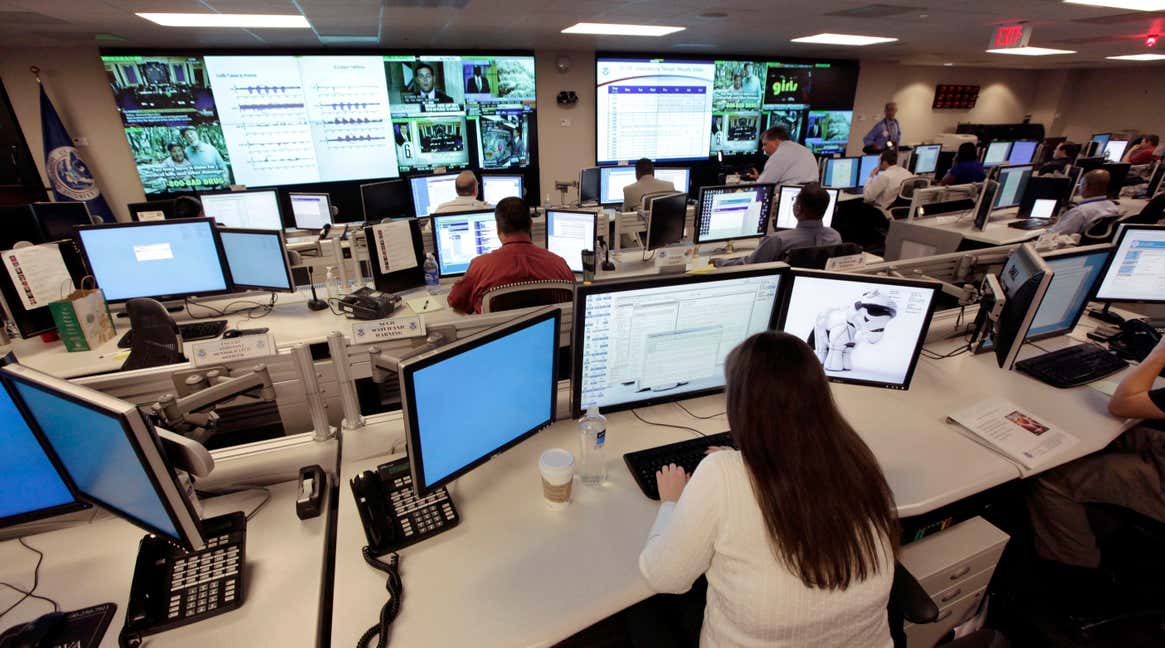

| Photo: J. Scott Applewhite (AP) |

A new kind of community is needed to flag dangerous deployments of artificial intelligence, argues a policy forum published today in Science. This global community, consisting of hackers, threat modelers, auditors, and anyone with a keen eye for software vulnerabilities, would stress-test new AI-driven products and services. Scrutiny from these third parties would ultimately “help the public assess the trustworthiness of AI developers,” the authors write, while also resulting in improved products and services and reduced harm caused by poorly programmed, unethical, or biased AI.

Such a call to action is needed, the authors argue, because of the growing mistrust between the public and the software developers who create AI, and because current strategies to identify and report harmful instances of AI are inadequate.

“At present, much of our knowledge about harms from AI comes from academic researchers and investigative journalists, who have limited access to the AI systems they investigate and often experience antagonistic relationships with the developers whose harms they uncover,” according to the policy forum, co-authored by Shahar Avin from Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk.

No doubt, our trust in AI and in AI developers is eroding, and it’s eroding fast. We see it in our evolving approach to social media, with legitimate concerns about the way algorithms spread fake news and target children. We see it in our protests of dangerously biased algorithms used in courts, medicine, policing, and recruitment—like an algorithm that gives inadequate financial support to Black patients or predictive policing software that disproportionately targets low-income, Black, and Latino neighborhoods. We see it in our concerns about autonomous vehicles, with reports of deadly accidents involving Tesla and Uber. And we see it in our fears over weaponized autonomous drones. The resulting public backlash, and the mounting crisis of trust, is wholly understandable.

In a press release, Haydn Belfield, a Centre for the Study of Existential Risk researcher and a co-author of the policy forum, said that “most AI developers want to act responsibly and safely, but it’s been unclear what concrete steps they can take until now.” The new policy forum, which expands on a similar report from last year, “fills in some of these gaps,” said Belfield.

To build trust, this team is asking development firms to employ red team hacking, run audit trails, and offer bias bounties, in which financial rewards are given to people who spot flaws or ethical problems (Twitter is currently employing this strategy to spot biases in image-cropping algorithms). Ideally, these measures would be conducted before deployment, according to the report.

Red teaming, or white-hat hacking, is a term borrowed from cybersecurity. It’s when ethical hackers are recruited to deliberately attack newly developed AI in order to find exploits or ways systems could be subverted for nefarious purposes. Red teams will expose weaknesses and potential harms and then report them to developers. The same goes for the results of audits, which would be performed by trusted external bodies. Auditing in this domain is when “an auditor gains access to restricted information and in turn either testifies to the veracity of claims made or releases information in an anonymized or aggregated manner,” write the authors.

Red teams internal to AI development firms aren’t sufficient, the authors argue, as the real power comes from external, third-party teams that can independently and freely scrutinize new AI. What’s more, not all AI companies, especially start-ups, can afford this kind of quality assurance, and this is where an international community of ethical hackers can help, according to the policy forum.

Informed of potential problems, AI developers would then roll out a fix—at least in theory. I asked Avin why findings from “incident sharing,” as he and his colleagues refer to it, and auditing should compel AI developers to change their ways.

“When researchers and reporters expose faulty AI systems and other incidents, this has in the past led to systems being pulled or revised. It has also led to lawsuits,” he replied in an email. “AI auditing hasn’t matured yet, but in other industries, a failure to pass an audit means loss of customers, and potential regulatory action and fines.”

Avin said it’s true that, on their own, “information sharing” mechanisms don’t always provide the incentives needed to instill trustworthy behavior, “but they are necessary to make reputation, legal or regulatory systems work well, and are often a prerequisite for such systems emerging.”

I also asked him if these proposed mechanisms are an excuse to avoid the meaningful regulation of the AI industry.

“Not at all,” said Avin. “We argue throughout that the mechanisms are compatible with government regulation, and that proposed regulations [such as those proposed in the EU] feature several of the mechanisms we call for,” he explained, adding that they “also want to consider mechanisms that could work to promote trustworthy behaviour before we get regulation—the erosion of trust is a present concern and regulation can be slow to develop.”

To get things rolling, Avin says good next steps would include standardization in how AI problems are recorded, investments in research and development, establishing financial incentives, and the readying of auditing institutions. But the first step, he said, is in “creating common knowledge between civil society, governments, and trustworthy actors within industry, that they can and must work together to avoid trust in the entire field being eroded by the actions of untrustworthy organisations.”

The recommendations made in this policy forum are sensible and long overdue, but the commercial sector needs to buy-in for these ideas to work. It will take a village to keep AI developers in check—a village that will necessarily include a scrutinizing public, a watchful media, accountable government institutions, and, as the policy forum suggests, an army of hackers and other third-party watchdogs. As we’re learning from current events, AI developers, in the absence of checks and balances, will do whatever the hell they want—and at our expense.

More: Hackers Have Already Started to Weaponize Artificial Intelligence.